Choosing wrong materials can ruin your PCB’s functionality. Thermal failures, signal loss, and mechanical breakdowns often trace back to improper material selection. But how do we avoid these pitfalls?

PCB stackups[^1] combine conductive copper layers with dielectric substrates (like FR-4, polyimide, or Rogers laminates) and adhesive prepregs. Material choices balance thermal stability, signal integrity, and cost. For example, high-speed designs[^2] need low-loss materials, while flexible circuits require bendable polymers.

Materials define a PCB’s performance, but the details matter. Let’s break down key considerations for core/prepreg selection, high-speed vs high-temperature applications, copper weight impacts, and flex PCB requirements.

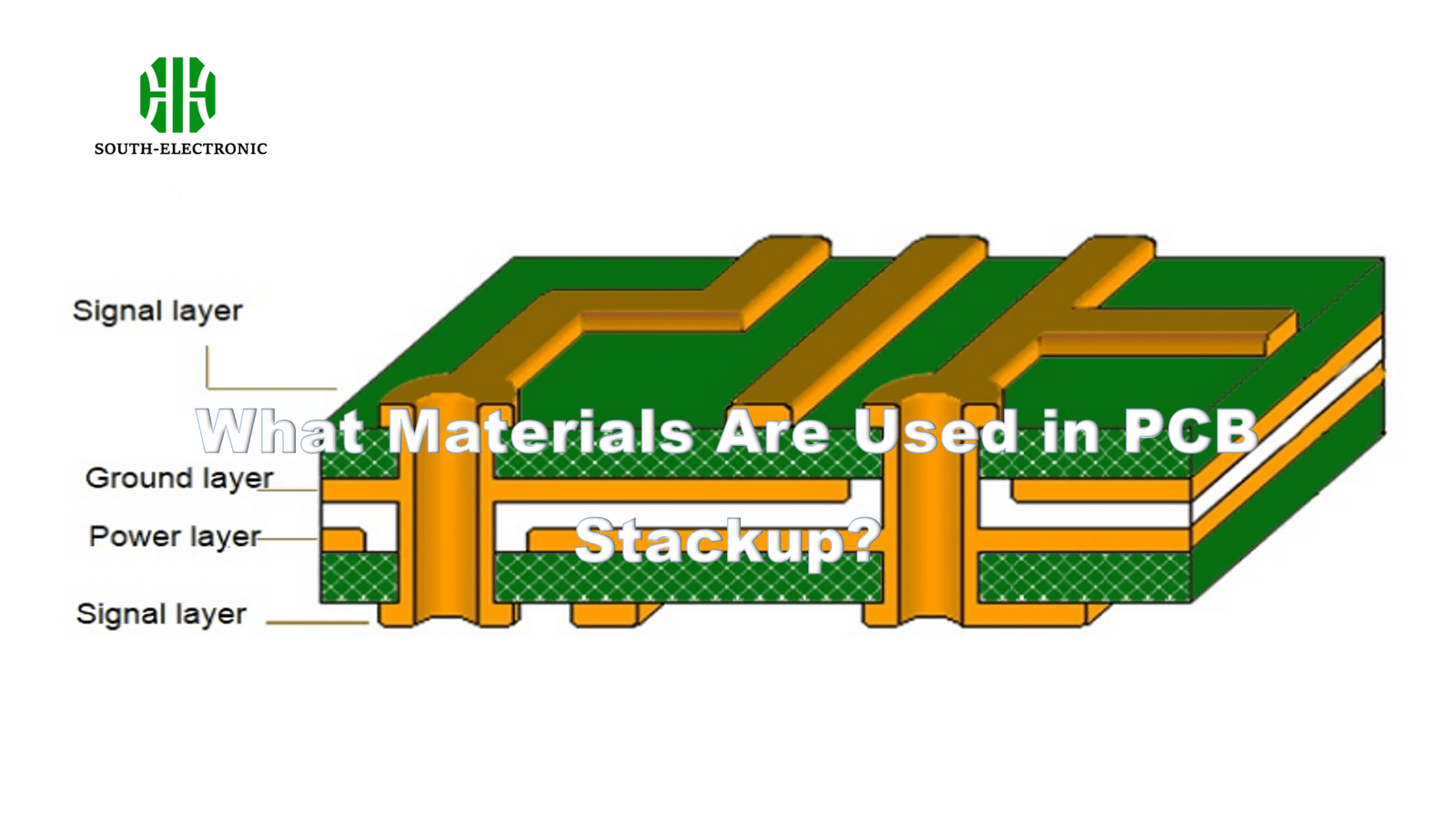

What Are Core vs. Prepreg Materials in PCB Stackup?

Mixing up core and prepreg materials[^3] leads to delamination risks. Designers often confuse their roles. What’s the functional difference?

Cores are rigid dielectric layers with copper foil (e.g., FR-4 sheets), while prepregs are semi-cured adhesive resins bonding cores. Cores provide structural stability, and prepregs enable multilayer stacking through lamination.

)

Key Differences Between Core and Prepreg

| Feature | Core | Prepreg |

|---|---|---|

| State | Fully cured | Semi-cured (B-stage) |

| Function | Structural base layer | Adhesive for layer bonding |

| Copper Bonding | Pre-attached copper foil | No copper (applied during lamination) |

| Thickness | Fixed (e.g., 0.2mm, 0.4mm) | Adjustable via resin content |

Cores act as standalone layers, while prepregs flow during lamination to fill gaps. For high-Tg applications, use cores with glass transition temperatures above 170°C. Prepreg resin content (e.g., 50%-60%) affects dielectric thickness and impedance control. A 6-layer board might stack: Core → Prepreg → Core → Prepreg → Core.

How to Choose Dielectric Materials for High-Speed vs. High-Temperature Applications?

A 5G antenna PCB failed due to signal loss. The culprit? Wrong dielectric material. How do we match materials to application needs?

For high-speed designs (>1 GHz), use low-loss laminates[^4] like Rogers RO4350B (Dk=3.48, Df=0.0037). For high-temperature environments (e.g., automotive), choose FR-4 with Tg > 180°C or polyimide[^5] (Tg ~260°C).

)

Material Selection Guide

| Application | Material Options | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|

| High-Speed | Rogers RO4000, Isola I-Speed | Low Df ( 180°C, CTE < 50 ppm/°C |

| Cost-Sensitive | Standard FR-4 | Dk=4.5, Df=0.02, Tg ~130°C |

High-speed signals demand materials with minimal dissipation factor (Df)[^6] to reduce attenuation. For example, Rogers RO4835 reduces loss by 30% vs FR-4 at 10 GHz. In high-temperature settings, polyimide handles repeated thermal cycles but costs 3x more than FR-4. Always cross-check manufacturer datasheets for CTE and moisture absorption.

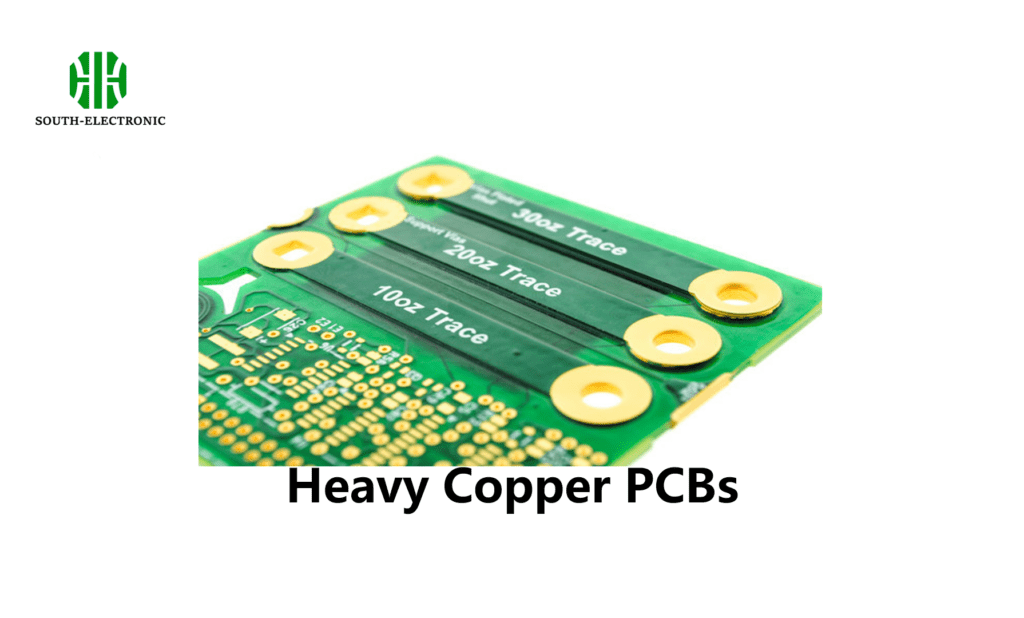

Does Copper Weight Impact Signal Integrity in PCB Stackup Design?

A 2-ounce copper design caused impedance mismatches, delaying a product launch. How thick should copper be for optimal performance?

Heavier copper (≥2 oz) increases current capacity but worsens skin effect loss at high frequencies. Use 0.5-1 oz copper for signals above 5 GHz and 2-3 oz for power planes.

Copper Weight vs. Signal Performance

| Copper Weight[^7] | Thickness (µm) | Best Use Case | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 oz | 17.5 | High-speed traces (5-20 GHz) | Limited current capacity |

| 1 oz | 35 | General-purpose signals | Moderate loss at 10+ GHz |

| 2 oz | 70 | Power/Ground planes | Impedance control challenges |

Thicker copper lowers resistance (R = ρ/(thickness × width)) but increases parasitic capacitance. A 1 oz copper trace at 10 GHz has ~0.15 dB/inch loss, while 2 oz adds ~0.25 dB/inch. For hybrid stacks, use thin copper for signal layers and heavy copper for power distribution.

Why Do Flex PCBs Require Different Stackup Materials Than Rigid Boards?

A rigid PCB material snapped after 200 bending cycles in a wearable device. Flex circuits need entirely different material strategies.

Flex PCBs use polyimide films (e.g., DuPont Pyralux) instead of FR-4. These materials withstand repeated bending (5000+ cycles) and have lower Young’s modulus (5 GPa vs FR-4’s 20 GPa).

)

Flex vs. Rigid PCB Material Comparison

| Property | Flex PCB Material | Rigid PCB Material |

|---|---|---|

| Base Dielectric | Polyimide (12-25 µm) | FR-4 (100-400 µm) |

| Adhesive | Acrylic or epoxy | High-Tg epoxy |

| Bend Radius | 6x material thickness | Not designed for bending |

| Thermal Conductivity | 0.12 W/mK | 0.3 W/mK |

Polyimide’s flexibility comes at a cost: it absorbs 1.5% moisture (vs FR-4’s 0.1%), requiring baking before assembly. Adhesives in flex stacks are thinner (10-25 µm) to maintain pliability. For dynamic flexing, use rolled annealed copper (RA) instead of electrodeposited (ED) copper to prevent cracking.

Conclusion

PCB material selection hinges on electrical, thermal, and mechanical needs. Match dielectric properties to signal speeds, copper weight to current demands, and base materials to rigidity/flexibility requirements for reliable performance.

[^1]: Understanding PCB stackups is crucial for optimizing performance and avoiding common design pitfalls. Explore this link for in-depth insights.

[^2]: Choosing the right materials for high-speed designs can significantly enhance performance. Discover expert recommendations and insights here.

[^3]: Grasping the differences between core and prepreg materials is essential for effective PCB design. This resource will clarify their roles and applications.

[^4]: Explore this link to understand the benefits of low-loss laminates in enhancing signal integrity for high-speed applications.

[^5]: Discover why polyimide is a preferred choice for high-temperature environments and its impact on performance.

[^6]: Learn about the critical role of dissipation factor in minimizing signal loss and improving PCB performance.

[^7]: Understanding copper weight is vital for optimizing PCB design, impacting signal integrity and thermal management.